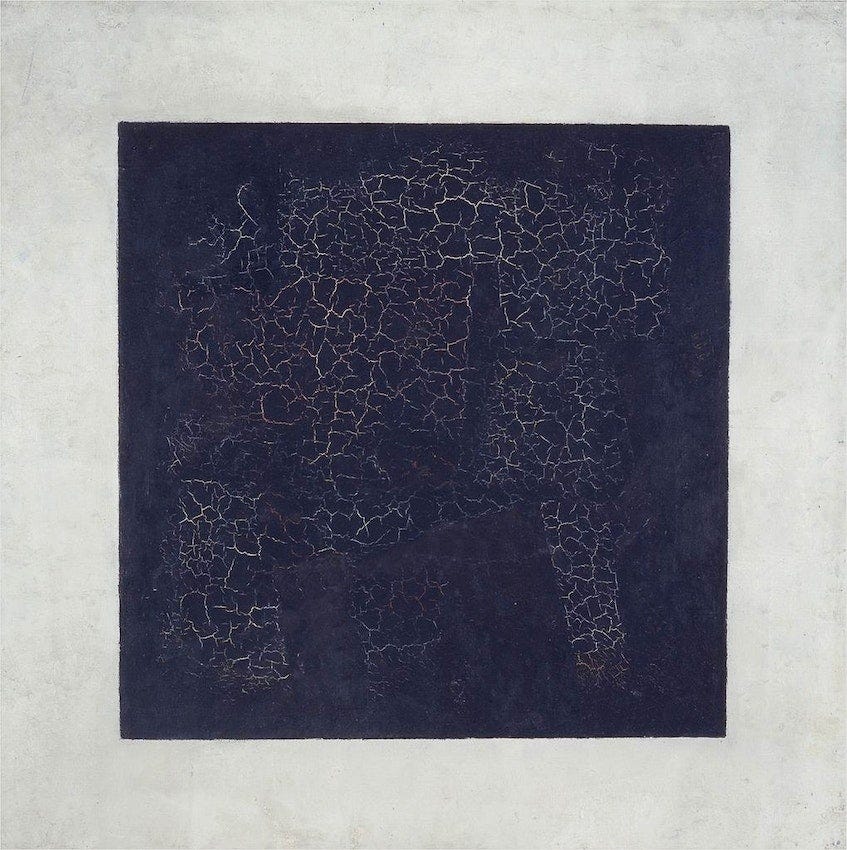

[I wrote a long introduction to this piece, then decided that it would speak most effectively in absentia.]

…which I suppose is sufficient explanation for the past six weeks, during which I found myself utterly unable to write. Of what relevance is the first-person form under such conditions?

Still, I was fussed. It is, after all, the inclination of writers to fuss about not writing, to think of silence as a problem. So when I boarded the train on a recent Thursday afternoon for a long run up the western face of Manhattan, I was hoping this problem might be solved by sustained aerobics, the smell of the Hudson, and the echoic clank of the water against the pier.

There I was: huffing and puffing northward through a downtown riverside park so clean it looked like an architect’s digital rendering, its grassy hillocks perfectly green, its concrete benches pressure washed to a gleaming white. Heart pounding. House music in my ears, and the treasonous kiss of a balmy November afternoon on my skin.

And then a thought came to me. It did not solve the problem of silence; it dissolved the problem. It emerged, appropriately, as if out of thin air.

It was this: writing is an active expression of experience. Some experiences can only be expressed through silence. Therefore, silence is a mode of active expression. In effect, and strangely, not-writing is a form of writing!

…or, to state it more pointedly: all of you readers of Radicle Weft received my silence over the past six weeks. Perhaps you did not notice this silence or the way it moved you. But it did move you. Not in the same direction as language might have done so, but with equal intensity. (As your respective silences have moved me in return.)

…or, to state the notion more broadly, I’ll quote the acoustic biologist Gordon Hempton, courtesy of Jenny Odell:

“Silence is not the absence of something but the presence of everything.”

It is common enough to say some insight or another took the air from our lungs; this was the first time that an idea put the air back into my lungs. I believe the implications of this insight can do the same for others. So let us give it our full attention:

The thought of silence as a presence confounded my prior understanding of silence and sound as mutually opposed, according to which sound is the presence of something, while silence is the absence of something, i.e., is nothing.

This distinction, if we sit with it, can reveal a great deal about the world we have made for ourselves. It is, at its heart, a matter of ontology.

Ontology. I use this word as anthropologists Terry Winograd and Fernando Flores define it: “our understanding of what it means for something or someone to exist,” and by extension, what it means for something or someone not to exist.

This, Winograd and Flores contend, is the most basic structure of our reality. If you wanted to understand the world on its most fundamental level, you would zoom out past history and culture and economics and geography and theology and you would find yourself looking at this — the logic by which we collectively determine what does and does not exist.

Ontology is a way of thinking about the world. But it is also a way of thinking about worlds — that is, about the possibility that there are many worlds on this single planet of ours.

If the thought of many worlds is hard to wrap your head around, there’s good reason for that: like me, you have been powerfully conditioned to believe that there can only be one world. It’s the one that most of us (barring my loyal Yanomami readership) inhabit on a daily basis.

I’m talking about the world that people of my political persuasion might characterize as Western, patriarchal, capitalist, colonial. It’s the world that has given rise to the forces cooking our planet. It’s also the world that most powerfully insists that it is the only one possible (what theorist John Law calls the “One World World”).

This is why the very notion that there can be multiple worlds (famously asserted by the Zapatistas : un mundo en que muchos mundos quepan) is so hard for Westernized people like me to compute. But the logic asserting that there is only one world is the same logic asserting that the ecological, social, and spiritual destruction all around us is inevitable. Natural. That all this pain is simply the way things are. Law’s acronym is fitting: OWW.

Ontology is a useful frame because it allows us to think more broadly about what we are talking about when we talk about the “world.” By defamiliarizing the terms of our shared existence, ontology allows us to see it as one of many possibilities. This way of thinking can afford proper place to the lifeways of indigenous peoples, whose (non-monolithic) insistence on modes of existence beyond global capitalism is, in my view, of literally existential urgency.

But wait. I started this piece with silence, and now I am yammering. So let me take a step back. We don’t need million-dollar words like ontology to understand this stuff. We already know it! Most of us, at least, have felt it in our variously sleep-deprived, chronically distracted, over-medicated bodies: the bone-deep sense that the world we live in was not built for our well-being. (This is true for even the most privileged among us, including your dutiful cis white male correspondent). The feeling that what we’re told is real is not really real — or at least, that it’s not the only real thing out there.

One of the humans writing most clearly about this dissonance (and there are many, many others) is Jenny Odell. Her book, How to Do Nothing, is to thank for the quotation that started this piece.

Odell’s argument is basically ontological, although she doesn’t use the term. It goes something like this: The incursion of digital technologies on our lives has had terrible consequences. It has made us lonely, over-worked and numb to the destruction of our planet and each other. And more than anything, it has powerfully curtailed our individual and collective ability to choose what is real. We are so overwhelmed with information and notifications that we have nearly forgotten that our attention belongs to us, and that we can decide what to do with it. Because it is our attention, Odell suggests, that sets the terms for the ontological world we inhabit. By placing my attention upon something, I say: this exists.

Thus, her wonderful title. How to do Nothing is not, as Odell notes, about doing “nothing.” It’s about doing all sorts of things that have been rendered non-existent by the dominant logics of digital platform capitalism. It’s about using your attention not just to imagine alternative worlds, but, by redefining the terms of what it means “for something or someone to exist,” to create those worlds ontologically.

Consider silence. Not the absence of something, but “the presence of everything.” Silence’s relegation to non-existence in the sound/silence dualism has produced a world where we are obligated to express ourselves (our “self”) but denied the conditions of quiet interiority needed to form that self in the first place.

This is a structural critique, not a personal one. I’m not throwing shade at the friend insisting on social media that “silence is violence.” She’s almost certainly right: silence is violence. But this is because the world has been built that way. The mechanisms of power that spend our taxes and wage our wars are not configured to hear silence, or to make meaning of it, or to recognize it as “the presence of everything.” The failing is not with silence, for being inscrutable to power, but with power, for being deaf to silence. We have built the wrong kind of power.

There are few words that can get you in greater trouble than “we.” But I use it intentionally. Not to imply some universal, undifferentiated responsibility for the shitshow we’re living in, but to insist upon the promise of individual and collective agency. If Winograd’s and Flores’ ontological frame is worth taking seriously, it means that our world-building ability hews both ways. Any time that we surrender our attention to the dominant paradigms of what does/does not exist (reinforced by the lucrative algorithms that populate our digital lives), we are making that world more inevitable. Fuel to the flames. But as soon as we willingly direct our attention otherwise, we bring new possibilities into the world — no, no, better to put it this way: we are bringing other worlds onto the earth. Especially when we do so in community.

Silence seems like a good place to start. I suppose simply because it’s there. Hear it? I am beginning to hear silence, although most of the time I don’t know what to make of it. I lack the ear for these fugitive presences; I have not been taught their language.

But I can learn! Indeed, as soon as I began looking, I found myself surrounded by the work of artists and writers and leaders seeking to find meaning in silence: Saidiya Hartman and Yasmine El Rashidi and Valeria Luiselli and John Cage come to mind. And those are just a few of the well-known ones; most teachers of silence will never be known to more than a few close relations. This anonymity doesn’t diminish what they have brought into the world. If anything, it raises the stakes of our work, as listeners and as students.

These guides are scattered, for the most part. They do not unite under the banner of SILENCE EDUCATION; many of them rarely use the word. They operate, as it were, in their own sort of silence. Which may be for the best. But those of us interested in learning to attend to silence would do well to know what tools can serve us.

It is, therefore, with full awareness of the contradictions therein that I propose an impossible undertaking: the creation of a Catalog of Silence.

This Catalog1 will be an exhaustive inventory of the forms of silence and their related forms of interpretation. It will be open-source and attended by a team of devoted volunteers. It will comprise entries on silences of the ecological, conversational, topographical, archival, architectural, typographical, sociological, digital, historical, acoustical, relational, geographical, marital, interplanetary, medical, textual, filial, and spiritual varieties, (among others). It will be a material artifact of collective and sustained attention to every thing and place and person which has been previously deemed non-existent. It will be very, very long. It will be universally accessible and free of cost. It will be one of humanity’s great achievements and the birthright of every child. It will be apparent to you if you listen.

The Catalog of Silence will contain all possible worlds.

Familiar readers will know I’m partial to this kind of conceit. See my essay on the Encyclopedia of Light.

This is beautiful.

One of my favorite novels is anchored in the presence of silence: The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. It opens with a passage on it, so even a downloaded sample will give you a taste. I highly recommend the passage and the book to any of your readers.

Regarding the catalog, I am very much for it. I am currently looking for ways to live into things other than my digital dopamine hits. I find that simply rejecting them does nothing to boost my morale, willpower, or joy in life.

Cataloging the silences seems to me to be a proactive way to create a different way of being in the world, or world to be in, as you might say.

Let us know how we can contribute.