[Friends — Happy New Year! It’s been a minute. Future hindsight will evidence, I trust, the wisdom of my launching a blog precisely at the moment that my writerly self-regard began to wobble. Most of what I’ve managed to conjure these past few months has ended up being a reflection on my inability to write, or on the insufficiency of language (or my insufficiency to it) — exercises in self-diagnosis.

But we are pressing on! And so I share with you this, the first of four installments on the relationship of poetics to infrastructure (hint: form). I have not written the latter two segments. Which makes this my equivalent of those poor souls who sign up for reality TV seeking in public exposure an accountability that they hope will get their ass into gear and their marriage / career / bodies into shape. Not to mention this is my second consecutive Hell-themed essay…

All of which belies the fact that my immediate sphere of life is, actually, pretty good these days, global catastrophes notwithstanding. So here we go — into the fiery depths…

(And as always, email me: <rustmenagerie@gmail.com>)]

1.

Let’s begin with an ending. Copied below is the final passage of Italian fabulist Italo Calvino’s small and beautiful book, Invisible Cities:

The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.

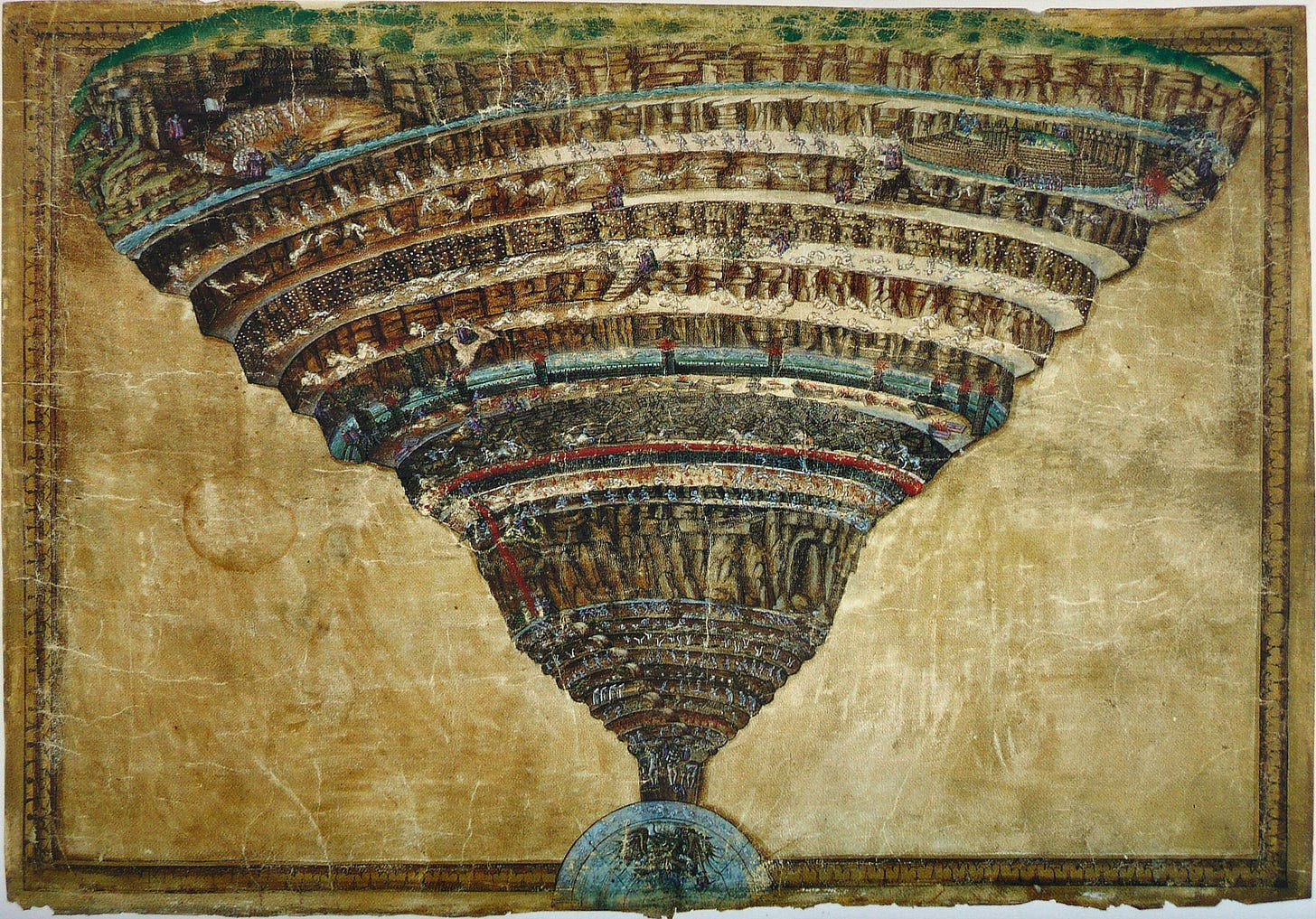

Calvino writes in Italian. His book is about cities. It’s fitting, then, that Invisible Cities, composed in the long shadow of the great Italian poet, Dante Alighieri, would retrace that shadow back to the gates of Dante’s seven-ringed city of the underworld. We’re talking about Hell here, or some version of it.

The sentiment of this passage will be familiar to most readers. In fact, it has become a sort of commonplace that, if Hell does exist, it exists here on earth, in our shared human world.

To resist Hell, writes Calvino, requires vigilance and apprehension1; it also requires discernment and care. If we think of this in political terms, it is a politics of attention. By this I mean that it describes a method of engaging with the world that is principally concerned with one’s ability give attention to the people and things in the world around them which are nurturing and just, and to cultivate them, and to help them grow.

The politics of attention are what you might call infra-political — that is, they create the conditions for what we might typically think of as politics. For there to be a dispute among parties, there must be a common object of dispute (something that the parties are disagreeing about). For there to be a common object of dispute, there must be a shared regime of attention, i.e. the parties must be giving their attention to the same thing and agreeing that it is real.

The establishment of common reality is therefore the goal of the politics of attention, and the departure point of all other political pursuits. It is fitting that Calvino’s work, a fable dancing at the edge of fantasy, should be concerned with the questions: What is real? And how do we care for it?

This question weighs heavily on the mind of Kubla Khan, the ruler of the Mongols, whom we find sitting in his pleasure garden in Xanadu. There, beneath the hanging lanterns of the cedar groves, he receives envoys, ambassadors and explorers from across his vast empire.

Kubla Khan faces the problem inherent to every builder of empire: the vastness of his realm far exceeds his ability to see, or even imagine its inhabitants.2 He must rely on the stories of the envoys he sends to the far reaches of his land, of whom his favorite is that footloose Venetian, Marco Polo.

When Polo visits the Khan, he describes the distant cities he has visited on his travels: wondrous places full of spiral staircases and green canals and markets full of astrolabes and bergamot and amethysts.

But shortly it becomes clear that Polo is less interested in the cities he describes — if, indeed, they even exist — than he is in probing the nature of places, and our experience of them, and the tools, like language, that we use to represent that experience.

Polo recalls the city of Tamara, where the streets are so thick with signboards that the traveler wonders whether he is experiencing the city or its own self-representation. Or the spider-web city of Octavia, strung above a precipice, where the precarity of the city’s inevitable collapse is, paradoxically, a source of existential certainty for its inhabitants. Or Thekla, where the city’s builders pause their labor at dusk to refer to their blueprints in the nighttime constellations.

The cities that Polo recounts to the Khan are ideas more than they are places; they represent cities’ universal qualities; they are (as he puts it) a “discourse” in need of interpretation.

In short, they are literary things that beg literary questions. By this reasoning, one could argue that Invisible Cities is not about cities at all, but is, rather, about the nature of representation and experience.

Okay, sure. But we are talking about the Inferno here — Calvino’s Inferno, and also our own (which is real, and literally aflame). And while the Inferno is certainly a metaphor (for punishment, for suffering, for sin), it is also a place. The point with which Calvino ends his book and we begin this essay is that that place is here: where you are, where I am, right now! That our ability to resist the Inferno relies upon recognition of this simple fact.

If that’s the case, this postmodern maneuver seems to me a step in the wrong direction: that sublimating any talk of concrete places into metaphors and discourses carries us further from the world of material things and beings that sustains us. After all, dematerializing our living environment has long been a method of abandoning our responsibility to that environment and the people in it.

This critique could just as well apply to the politics of attention in general: that it can be indulgent and deluded and solipsistic and escapist. That it permits us, in its crudest manifestation, to focus on perceiving without ever actually doing anything. That it mistakes a shift in our experience for a shift in material conditions.

But this would, I think, be giving too little credit to its possibilities.

So let us be generous. Because the first step (and only the first!) of Calvino’s program is: seek and learn to recognize. Discern. And literature — particularly forms of literature considered outdated, like myth and epic and folklore3 — can indeed be instructive in this respect. It can give us tools to see, and to more precisely attend to those obscured faces of our surroundings which require our care and attention.

[Onward! Read Selling Sky (2/4) here…]

The translation of this cognate is a little clunky; in English, it’s not clear whether this should be taken to mean “misgiving” or “awe” or “understanding.” I suspect that the word in Italian more smoothly encompasses all three. Maybe LN or MH can clear this up for me.

See James Scott’s Seeing Like a State.

See Matthew Spellberg’s Myth Lessons for an awesome essay on the role of mythic and epic literature in contemporary prison education.